Disclaimer: This is not a sample of our professional work. The paper has been produced by a student. You can view samples of our work here. Opinions, suggestions, recommendations and results in this piece are those of the author and should not be taken as our company views.

Type of Academic Paper – Dissertation Chapter

Academic Subject – Economics

Word Count – 7498 words

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) played a vital role in the economy and are considered significant in driving innovation and offering competition to large industries in many sectors. However, reliable decision-making processes are needed to provide competition in the areas of innovation and market development. On the other hand, Kim et al. (2014) added that many factors affect SMEs’ decisions in the area of innovation based on market drivers and constraints. This literature review addressed the main issues faced by SMEs in driving success through innovation and how external support from marketing and IT consultants, information technology (IT) experts and other resources supports the innovation-led SMEs.

The focus of innovation strategies and the barriers faced, by SMEs in technology-led innovation is also given in the review. The literature in the period 2005 till present is considered to keep the research relevant and updated. There are several studies found on the innovation strategies of SMEs in recent years. Still, there is no comprehensive literature review found on the supporters of innovation in SMEs. Therefore, this research aimed to examine the current research on innovation in SMEs and integrate the empirical findings of several studies.

Given Jafari et al. (2007), SMEs can be defined through quantitative and qualitative parameters. The subjective or qualitative parameters of defining SMEs are related to the low scale of production and small to medium operations. In contrast, quantitatively SMEs can be determined by using the size of the organization. The other standards, including sales turnover, employees’ turnover, and the invested capital of business, are commonly used in developed countries. The definition forwarded by EU policies and in APEC economies is based on the number of employees that SMEs are the organizations that employ around 100 to 500 employees. The other criteria for defining SMEs are rated to the level of competition in the industry, and the rapid globalization of the markets played an important role in increasing the organisation’s size and scale. The service led sectors and technology-dependent sectors to improve on the scales of operations without increasing the employees’ base.

Therefore, multiple factors should be considered to consider the size of the business other than employees’ only. Moreover, Dadfar et al., (2013) asserted that the rapid advancement of technology and the decline in the product and technology life cycles force the SMEs to invest more innovations to gain a competitive advantage. Moreover, Dadfar et al., (2013) also concluded that SMEs are drivers of innovation and play a significant role in major economies of the world despite the common perception that innovations play an important role in large organizations success. According to Liu (2012), in Japan, Italy, and France, the share of SMEs is 995 of all organizations that show their pivotal role in these countries’ economic progress. Similarly, the US economy is supported by more than 2000 million SMEs, Contributing to 98% of the total organizations, though, the state is pronounced with the large enterprises globally.

The ample and diverse literature on innovation provided evidence for its importance in organizational progress. Schumpeter (1934) considered the pioneer of innovation in the literature (McAdam et al. 2014). Bayarçelik and Taşel (2012) explained Schumpeter’s concepts that new products, services, new markets, new consumers, and new modes of transportation are important to run the engine of the capitalist economy. Therefore, innovation is an essential component of organizations in the capitalist economy. Innovation has multiple ways of implementing improved products, renovated processes, restructured service design, and niche marketing methods for any organization or product. Thus, the latest modes of operations, handling human resources, and improved business practices are important facets of innovation. Similarly, Klewitz and Hansen (2014) stressed that successful innovations need enhanced diffusion of products in the market or implementing a process to attain the desired economic activity.

The literature suggested multiple ways of achieving innovation. The development of the company’s business strategy with an integrated development through improved market positioning, work organization, and better engagement of people. However, Theyel (2013) argued that due to local SMEs’ limited resources, the range of innovation implementation differs and restrict their attainment of competitive advantage through innovation.

In this perspective, Hyvonen and Tuominen (2006) argument is important that sustainable competitive advantage needs a vital source of the capability of innovation. Still, the link of innovation is mostly with intangible resources. Previous research of Rangone (1999) assisted through an innovation model that addressed the SMEs’ performance as a function of innovation, marketing, and operations capabilities.

The other famous school of thought for innovation is related to the Resource-based view. Penrose’s research is based on the interrelated concepts of the knowledge-based approach and the resource-based view. The latter is based on the useful utilization and allocation of available resources in a productive manner. In contrast, the criteria linked with the knowledge base perspective are based on the estimation of how the allocation and utilization of company resources are made (Hughes, 2009). The structure of the organization, management expertise and decision-making in the organization played an essential role in the resource-based view. Thus, learning and innovation enhance the capabilities of important drivers of RBV. This implementation of innovation depends on both internal and external factors. In another theory, dynamic capabilities are required to create innovation in the organization. Spithoven et al. (2013) asserted that the implementation needs dynamic competencies that assist in producing new sources of knowledge. However, organization adaptation to the environment changes is also important as these dynamic skills cannot be developed in isolation.

Chesbrough was the first to coin the term ‘open innovation in 2003. This theory is in the theoretical literature of innovation based on an encircling paradigm grounded upon longstanding and well-studied factors such as entrepreneurship, management, and innovation theories. Following are some of the theories that are identified as pillars of open innovation in an organisation, including SMEs (Brunswicker and Vanhaverbeke, 2015).

Eric von Hippel (1986, 1988 cited in Davis and Brady, 2015) proposed the user innovation theory and concluded that consumers and users of a business’s products are the real and most important source of innovative ideas for new product development. In his theory, Von Hippel concluded that there are four external sources of innovation and knowledge for a business, which are:

The author argued that there is a c0-development process for most new products and services, or at least the process of new product development is refined due to the involvement of customers. The author cited various other authors who had made similar conclusions and concluded that there is a tendency in firms to use networking, alliances, joint ventures and licensing agreements, and arms-length and informal relationships as an effective source of finding and incorporating expertise from external sources and knowledge to facilitate innovative processes in the company (Brunswicker and Van de Grande, 2014).

The seminal work presented by Teece (1986, cited in Rasheed, et al., 2017) was focused on increasing profitability from the innovation process infirm. The work showed that first movers in the industry might be poorly positioned in the market. Therefore, new entrants or competitors can gain higher economic returns by identifying new and more innovative competitive advantages. The theory states that those regimes of Appropriability, in other words, environmental factors, are the main factors that affect firms’ ability to profit from the innovation. Furthermore, Teece also noted that efficiency and efficacy of existing legal mechanisms in the country for the protection of innovative ideas (mainly the intellectual property rights) could be used to identify two regimes of innovation:

When there is adequate protection for businesses to protect their technology, they tend to put in more effort to develop new technologies and profit from them. Thus innovation is promoted. In contrast, when legal protection is ineffective and counterfeit products and technologies are common, innovation is discouraged in the business world (Singh, 2015).

Cohen and Levinthal (cited in Wynarczyk, Piperopoulos, and McAdam, 2013) initially refined the Absorptive capacity theory. They described it as the ability of a business to identify and value external and new information, assimilate it, and use it for commercial gains. The authors concluded that the fundamental factor for acquiring and utilising external technology and knowledge is the investment dedicated to a firm’s internal R&D facilities. Later, Bloch and Bhattacharya (2016) enhanced this theory and added four distinguished dimensions in a firm’s absorptive capacity, namely, acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation. It was found that investment and development in internal R&D capacity (in terms of both human and capital resources) remain the main and most important component of a firm’s absorptive capacity. It has a high impact on advancement in technology, new product development and innovation, utilising and accessing external technology and knowledge, competitiveness and international success, among others, The authors concluded that to become an innovation-oriented business, a firm must ensure that it focuses on continuous learning and ensure effective flows of knowledge, information, and ideas in and out of the company. Furthermore, the R&D of a firm cannot solely rely upon internal developments grounded upon internal knowledge sources. Instead, the firm must identify and use external sources to generate and incorporate knowledge (Grimaldi, Quinto, and Rippa, 2013).

Penrose (1959, cited in Halme and Korpela, 2014) developed the joint resource-based strategy framework, and it was based on the conclusion that every firm has limited resources. The framework describes an effective model that shows that collaboration opportunities, transferring, and sharing knowledge are important factors for innovation. Later, several authors, have contributed to developing this theory further. Hossain (2015) recommended that collaborations, partnerships, and alliances offer important capacities for innovative capacities in a company (particularly for SMEs). They use these resources to develop a sustainable competitive advantage in high rivalry situations. Innovation attracts corporate partners and customers. Strategic alliances for firms to mutually cooperate have been identified as crucial elements in various, particularly capital-intensive and knowledge-intensive industries. In the industrial sector, strategic alliances can be observed as very prominent factors that promote new product development. At the same time, businesses share risks and costs of new product launches and consequently share benefits and profits. However, for a strategic alliance, sharing of knowledge and technology among partners is crucial.

For example, Williams and Tsiteladze (2016) conducted a study. They reported that around 60% of Japanese companies are highly dependent on external sources for technology, and 50% of the US firms were attempting joint ventures to promote alliances in the market. The primary aim of these alliances and joint ventures was to gain access to knowledge and new technologies. The author concluded that when the environment is turbulent and complex, and the businesses are highly dispersed, it is important for managers to consider collaborations with customers, suppliers, research institutes, universities, and even competitors, as an instrument to gain competitive advantage and seek innovation. The aim is to share internal resources with partners and gain access to their resources. These results in new synergies and enable managers to create, access, transfer and integrate new knowledge. Indeed, the author concluded that if a firm does not cooperate and exchange knowledge, there is likely that the firm’s level of knowledge will decrease in the long run. Consequently, it will lose the ability to develop effective relationships and partnerships with important stakeholders in the environment.

Orders completed by our expert writers are

There are multiple studies found in the application of innovation in SMEs. The research of Karpak and Topçu (2010) is based on the development of the framework of multiple criteria the estimate the success of SMEs in Turkey. The use of analytical network process (ANP) for manufacturing B+SMEs in this research concluded that there are five critical factors that played an essential role in the company uses, These factors include the external environment, the internal environment of the firm, the expertise of management, institutional support, and approach to innovation. In another study by Talebi et al. (2012), various types of change were identified, and their independent factors are attempting SMEs successes. On the other hand, another research of Iran found essential factors affecting innovation capacities of the firm are the stage of the industry, demand, and industry-university linkage, attitude toward change and size and age. Other studies in this area have developed further concepts and models to explain innovation performance and the factors that can influence said performance. For example, Chang et al. (2011) argue that to be genuinely useful at harnessing the power of external and open innovation; SMEs need to develop a high level of innovation ambidexterity, which refers to their ability to innovate simultaneously from both an internal and external perspective.

Another important reason for innovation importance is the advantage of financial performance and competitive ability linked to innovation’s success. Snoj, et al. (2007) added that it is hard to forecast the required changes in future markets and technologies despite this importance to innovation. Therefore, visible approaches in top management plays a vital role in devising policies for innovation in an organization to forecast the next situation, which was reviewed in various studies (Prajogo and Ahmed 2006). In this context, McEvily (2004) research prescribed two critical factors of innovation growth in an organization, the culture with innovation orientation and the organizational ability to enforce successful innovation in approaches, technology, and progressive techniques.

Despite the development of technology and support for open innovation collaborations, there are specific challenges for SMEs’ progress. The lack of managerial, technical and human resources create the major challenge for rapid progress in SMEs (Rahman and Ramos 2010). Also, Colombo et al. (2014) asserted that SMEs’ activity in open innovation was found less compared to the large organizations due to their lack of resources and lack of visionary approaches in organizational culture, strategy, and policies. OECD (2016) report on SMEs progress concluded that the active SMEs for open innovation are only 5-20% of the total SMEs in the economy. Therefore, there is fragmentation observed in the studies on open innovation in SMEs’ progress (Bianchi et al. 2010). However, some studies support the role of open innovation SMEs’ progress compared to the massive organizations since SMEs are flexible with less bureaucratic procedures that can hamper innovation in rapidly changing environments (Parida et al. 2012). Similarly, Gassmann et al. (2010) also supported that notion that open innovation is a means for SMEs to overcome their flaws and increase productivity. The presence of skilled human resources is an anointer barrier to developing open innovation approaches in SMEs (Comacchio et al. 2012). Despite external support from government and non-government sources, Henkel 2006) argued that internal development of human and technical resources restrict the SMEs effort’s to exploit available support in an external environment.

Furthermore, Abouzeedan et al. (2013) criticized the slow progress of SMEs in exploiting open innovation resources due to the resources scarcity, complexity of technology, lack of coordination, and inability to access a state of the art scientific resources. However, licensing and franchising of the SMEs’ progress through open innovation is not appropriate in the short term. It requires building up of reputation and testing the transferred knowledge to larger scales. Hence, SMEs cannot materialize their knowledge base readily in the presence of the large organization and their extensive resource base (Andries and Faems 2013). In this case, Christensen et al. (2005) argued that transactions costs involved in an exchange of open innovation resources are due to technology companies’ involvement and complicated procedures.

Brunswicker and Vanhaverbeke (2015) identified three main streams in the literature related to innovation in SMEs. The first is the economic oriented literature, the second is organization-oriented, and the third is project-oriented literature. Economically oriented studies are primarily focused on the fact that small businesses should be considered important driving factors of innovation. The degree of innovation in SMEs can be as much as large multinational enterprises. But the organisation-oriented studies largely recommend that there are only a limited number of factors that small business owners can use to improve the business’s performance, including using regional centres, networking, careful planning, and appropriate business development strategies. Likewise, organisation oriented literature also prescribes various methods through SMEs that could enhance innovation, for example, by optimizing organizational structure. The project-oriented literature concludes that the main source of innovation in SMEs is the customers. Brunswicker and Vanhaverbeke (2015) critiqued that innovation SME literature has a high level of diversity in focus. Therefore it is difficult to identify a universally accepted list of factors that affect innovation in the SMEs sector.

Davis and Brady (2015) also conducted a comprehensive review of SME innovation literature. They concluded that a variety of barriers had been identified in promoting innovation in SMEs, including variation in the degree of innovation processes, variation in typologies and types of innovative, innovation and diffusion types of market. The author also criticised that literature related to innovation management is often focused on hi-tech small firms and conducts analyses of the innovation process and innovation in the product development process. A review of the recent literature shows that there is a variety of factors that can effectively promote innovation in the company, for example, benchmarking and networking, Research and Development (R&D), and the degree of effective organizational learning.

Brunswicker and Van de Vrande (2014) showed that corporate leadership has a significant role in promoting innovation and translating it into its performance. The leadership is involved in developing a competitive structure and shaping strategic orientation. If innovative processes are integrated by the leadership in these two management functions, there is likely to be a positive impact on the company’s performance.

Overall, the literature related to factors that promote innovation in small and medium enterprises is diverse and fragmented. The majority of the studies are more focused on understanding the role of innovation management in the context of new product development and that innovation processes are often analysed in isolation. Many studies are based on field research design, using survey questionnaires and conducting case studies that have limited implications and application on the general population.

There are various means discovered in the literature to support open innovation processes in SMEs. Due to the variety of factors affecting innovation practices in SMEs, as discussed earlier, the role of collaboration and networking is essential.

The study of Spithoven et al. (2013) discovered that SMEs’ partnership with external organizations and agencies support their struggle to launch new services and products. Similarly, Parida et al. (2012) the vertical collaboration involved support for radical or disruptive innovation. The incremental change is supported, but the horizontal cooperation among various agencies and SMEs facilitated incremental innovation. However, Lecocq and Demil (2006) argued that vertical collaboration decreased SMEs’ size due to the adoption of the latest technologies and outsourcing that can easily share the workload. For instance, cooperation with call centres helps SMEs reduce the clerical staff and telephone operators. On the other hand, there is the inevitable collaboration that goes beyond the technical assistance and involves the partnerships in enhancing value chains efficiently (Spithoven et al. 2013).

Similarly, external agencies and consultants’ collaboration can be performed through open innovation that includes product or service development. In contrast, the incremental innovations in horizontal collaborations involved changes in the existing products (Wynarczyk 2013). In another study, the support for increasing innovation is essential in SMEs’ commercialization stages as early stages bed offerings of the same product or service for a long time (van de Vrande et al. 2009). Moreover, the SMEs’ external support for innovation is largely linked to the size of the organization (Hemert et al. 2013). For instance, small SMEs are less likely to achieve external support for innovation than the larger SMEs that have more room for gaining external collaboration (Teirlinck and Spithoven 2013).

Networking is one of the most current methods of getting support from the business and social environment in SMEs innovation processes (Lee et al., 2010). Nevertheless, Heger and Boman (2014) emphasized the partnerships developed through networking are limited to the use of collected data or support in some primary activities of decision making or strategy formulation. Given Sarasvathy (2007), the identification and recognition of entrepreneurship opportunities are primarily linked to the closed interlink with associate individuals and companies. Hemert et al. (2013) suggested that it is a common observation that SME innovation is largely inclined to the other SMEs and institutions.

In this respect, McAdam et al. (2014) asserted that horizontal networks collaboration demonstrated that knowledge-based networks and other social network constructs support more wisely in the case of horizontal collaborative networks. However, it can be argued that consideration of both informal and formal association is vital in making networks of business and social circles (Padilla-Meléndez et al., 2013). Nonetheless, Pullen et al. (2012) discovered a consistent and focused approach to networking to generate efficient innovation performance. The network profile presented in this study includes a complement of goals and resources and the requirement of low position strengths of networks and mutual trust. On the other hand, the study on networking by Suh and Kim (2012) argued that networking is not a practical approach to support innovation in SMEs since these organizations cannot balance the powers among many partners in networks.

Similarly, Török and Tóth (2013) declared that rather than using organizational networks, the approach of personal networking was found useful for SMEs as managing people is a challenging task at these SMEs of developing countries. The reason for this cautious approach of SMEs in building extensive and intensive networks found in the study of Hughes (2009) is that there is a tradeoff involved in creating these two types of networks for SMEs. Apart from this criticism on the networking approach of support for innovation in SMEs, Theyel (2013) found that the preference of networking with customers is more profound in SMEs than the networks of suppliers.

In this regard, Hronszky and Kovács (2013) suggested that living Labs agencies can provide useful innovation strategies by integrating SMEs in collaborative networks. Open innovation in the collaborative economy also posed valuable implications for innovation in SMEs. The example of IDEO provides an interactive and collaborative platform for SMEs to invite suggestions and plans for innovating products or services. Open competitions from professional agencies, experts, and students of universities can provide cost-effective and economic innovation support in the collaborative economy (Theyel 2013; Hronszky and Kovács 2013).

As published in the report published by the Organization of Economic and Cooperation Development in the Bologna Symposium, (OECD, 2000) Financing was marked as a major hurdle by these SMEs in conducting R& Ds for innovation novelty. Research can be expensive as it demands both time and finance to conduct, reducing profitability. Unfortunately, most SMEs, unlike large scale industries, have limited budgets that they find hard to categorize for research. As a result, these companies fail to access the completion of ideas, even if they might have innovative ideas.

The companies at this scale need a minimum capital to keep the functioning going. After dedicating most of their budget to the company’s running expenditure, they hardly can save some for research. Moreover, most of the Smaller Scale Industries do not have the technologies or the finances that can buy them the technologies they need for finances. Inadequate knowledge and knowledge assets are also one of the reasons for the limited access of SMEs to innovation. If supported or helped accordingly, these SME’s can also prove themselves the bringers and beginners of change, innovation and new technology.

One way that ensures the promotion of innovation and novelty in small and medium enterprises promise them that they reap the benefits of their innovation. Laws and administrative procedures should be so that promise the copyrights of innovation to its fore bringers. Even if all share the technology, a share in a profit should be given to the company that brings it forward. It is the intellectual property of a company or its inventor, and the company should benefit from it as its creator. When in the conference, (OECD, 2000), patents and copyrights laws were brought up, most SME representatives mentioned that either the laws had loopholes that made them too difficult to approach or too easy to breach. Or these laws dampened the flourishing and nourishment of the new idea, making it dead in some time.

The presence of consultants and non–government organizations (NGOs) to support innovation and development played a significant role. Access to opportunities largely depends on the availability of funds and required human resources. There are international initiatives such as Horizon 2020, the European Union’s initiative through an established ‘Enterprise Europe Network (EEN). EEN supports the SMEs in Europe to access required funds for new or existing projects and facilitate resource mobilization, capacity building, innovation management, and IPR management. Horizon 2020 supports improving SMEs’ funding access by providing brokerage services through the SME instrument of the European Innovation Council (EIC). Another important initiative for innovation support in EU countries is found in this EUREKA/Eurostars Joint Programme Initiative (2014-2020). This effort is responsible for providing funds for SMEs’ research and development activities in EU member states (Horizon 2020, 2017).

On the discussion of the raised issue, several interesting solutions have been proposed. This is an issue faced by many, and about that, a lot of people have given it a fair share of thought. However, most of these solutions proposed to require the governments’ support and favours and the controlling authority of the majority of the systems in the country.

It was proposed that as an incentive to be a taxpayer and that to a major amount in the country, these companies should have access to a common R & D centre where they can have their researchers work for innovative solutions to problems and help themselves as the government. These R&D centres should have access to information and technologies that these SMEs can’t have on their own or can’t afford. This solution demanded the construction of an R & D department of the government dedicated to SMEs.

Government and Public Universities can also be taken into the loop as they can be a prime source of research and innovative knowledge. Shared Knowledge is another important aspect and can be the key to the solution to this problem. Many companies with greater resources or better opportunities are successful in gaining information that others cannot lead them to an advantage in research. IF this data is shared, this might help speed up the research process. Moreover, some other company or its researchers might unravel or find out something that the company could not know.

With the shared platform, this discovery would be shared with the company that came up with the information first making a win-win situation for both. Training and educating the masses can also be considered important factors when it comes to innovation. Most of the individuals working in companies, though educated, are not trained to work for innovation and discovery. This too puts SMEs on a back foot as they cannot afford to hire specialist researchers. On the other hand, this training can make their employees well versed in research.

When it comes to the external agencies, the issues faced by these small industries have been discussed above that cause hindrance in the companies’ approach and access to innovation. However, in this case, the agencies also face some difficulties that wish to support the innovation in SMEs. One of the foremost challenges that the agencies’ face is finding and approaching the right SMEs because when it comes to financing and supporting, none of the masses would say no to it, however, it is the job of the company to make sure that they approach the right company for the hand that they want to extend with them towards innovation. Moreover, even if the right companies are targeted and spotted, it is enough to decide how they would be provided. The governments too, have limited resources and are answerable for what they consume. It could be in the form of training, finance or specialized personnel.

However, companies demand this aid in the form of their own liking. This too poses a challenge for the aid provider. Often the agencies have suggestions to provide to the SMEs, but not all companies agree with their suggestions and consider them null. This costs these agencies time and money and gets them no fruit whatsoever. When such an agency aims to support an enterprise, one of the significant procedural and technical issues faced is monitoring the functionality. Most SMEs are not very friendly and open to the aspect of their continuously monitored processing. On the other hand, it is vital for the supporting agency that the support provided is being used for good and applied correctly.

Before discussing non-collaborative innovation projects, a little light has been shed on collaborative innovation projects and demerits. It is not uncommon to have collaborative innovation projects considering the limited resources of companies for Research. Moreover, companies need to be fast in bringing the product to market from the beginning of its manufacture.

Suh and Kim (2014) found that SME’s find it more efficient to pursue non-collaborative innovation in the service sector, and it brings in significant advantages for SMEs in the service sector. Lee et al. (2010) stressed the importance of non-collaboration innovation during the commercialisation stage. They argued that it helps in new product development, which is the main problem of SMEs. They argued that collaborative innovation is mainly pursued when new product development requires resources that are not available. Theyel (2013) also reported results in similar lines and added that businesses that are using open innovation already for technology or new product development would prefer to complement their resources and knowledge related to commercialisation and manufacturing through open innovation strategies subsequently. It can be inferred that overall, the majority of existing literature is focused on the front end of innovation, and there is a tendency to ignore the commercialization process.

Lee et al. (2010) studies various types of collaborations in case of open innovation and grouped them according to firm relationships, which included strategic alliance, customer-provider, and inter-firm alliance. The main benefit of the customer-provider relationship is that it enables firms to extend their own capabilities quickly. For instance, firms can acquire technology from partners through in-licensing.

Abouzeedan, A, Klofsten, M, & Hedner, T. (2013). Internalization Management as a Facilitator for Managing Innovation in High-Technology Smaller Firms. Global Business Review, 14(1), 121–136.

Albors-Garrigós, J, Etxebarria, NZ, Hervas-Oliver, JL, & Epelde, JG. (, 2011). Outsourced innovation in SMEs: a field study of R&D units in Spain. International Journal of Technology Management, 55(1), 138–155.

Andries, P, & Faems, D. (2013). Patenting activities and firm performance: Does firm size matter? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(6), 1089–1098.

Bayarçelik, E.B., Taşel, F. (2012) Research and Development: Source of Economic Growth, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol.58, 12

Bloch, H. and Bhattacharya, M., 2016. Promotion of Innovation and Job Growth in Small‐and Medium‐Sized Enterprises in Australia: Evidence and Policy Issues. Australian Economic Review, 49(2), pp.192-199.

Brunswicker, S, & Ehrenmann, F. (2013). Managing open innovation in SMEs: A good practice example of a German software firm. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 4(1), 33–41.

Brunswicker, S, Vanhaverbeke, W. (2014). Open Innovation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management. doi:10.1111/job.12120.

Brunswicker, S. and Van de Grande, V., 2014. Exploring open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. New frontiers in open innovation, pp.135-156.

Brunswicker, S. and Vanhaverbeke, W., 2015. Open innovation in small and medium‐sized enterprises (SMEs): External knowledge sourcing strategies and internal organizational facilitators. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), pp.1241-1263.

Castro, G.M., Delgado-Verde, D., Navas-López, J., Cruz-González, J., (2013) The moderating role of innovation culture in the relationship between knowledge assets and product innovation, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, Volume 80,351–363.

Chang, S.I., Yen, D.C., Ng, C.S.P., and Chang W.T., (2012) An analysis of IT/IS outsourcing provider selection for small- and medium-sized enterprises in Taiwan, Information & Management, Volume 49, Issue 5, pp. 199-209.

Chesbrough, H, Vanhaverbeke, W, & West, J (Eds.). (, 2006). Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dadfar, H., Dahlgaard, J.J. , Brege, S., Alamirhoor, A. (2013). The linkage between organisational innovation capability, product platform development and performance. Total Quality Management, 24(7), 819 –834,

Davis, P. and Brady, O., 2015. Are government intentions for the inclusion of innovation and small and medium enterprises participation in public procurement being delivered or ignored? An Irish case study. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 28(3), pp.324-343.

EU (2016), Social Enterprises and their Ecosystems: Developments in Europe, European Commission, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (2016). Consultation on the EU Strategic Work Program 2018-2020. Horizon 2020 dedicated Expert Advisory Group on Innovation in SMEs. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupDetailDoc&id=25452&no=1

Fu, X. (2012). How does openness affect the importance of incentives for innovation? Research Policy, 41(3), 512–523.

Gassmann, O, Enkel, E, & Chesbrough, H. (2010). The future of open innovation. R&D Management, 40(3), pp. 213–221.

Grimaldi, M, Quinto, I, & Rippa, P. (2013). Enabling open innovation in small and medium enterprises: A dynamic capabilities approach. Knowledge and Process Management, 20(4), pp. 199–210.

Grimaldi, M., Quinto, I. and Rippa, P., 2013. Enabling open innovation in small and medium enterprises: A dynamic capabilities approach. Knowledge and Process Management, 20(4), pp.199-210.

Gunsel, A., Siachou E., Acar, A. Z.(2011) Knowledge Management And Learning Capability To Enhance Organizational Innovativeness, Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 24 , pp. 880–888.

Halme, M. and Korpela, M., 2014. Responsible Innovation toward sustainable development in small and medium‐sized enterprises: a resource perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(8), pp.547-566.

Heger, T, Boman, M. (2014). Networked foresight — The case of EIT ICT Labs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change.

Hemert, P, Nijkamp, P, & Masurel, E. (2013). From innovation to commercialization through networks and agglomerations: analysis of sources of innovation, innovation capabilities, and Dutch SMEs’ performance. The Annals of Regional Science, 50(2), pp. 25–452.

Henkel, J. (2006). Selective revealing in open innovation processes: The case of embedded Linux. Research Policy, 35(7), 953–969.

Hogan, S. J.,Coote, L.V. (2013), Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein’s model. Journal of Business Research, 4(3), pp. 1-13.

Horizon 2020 (2017), Innovation in SMEs, accessed from https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/innovation-smes.

Hossain, M., 2015. A review of the literature on open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 5(1), p.6. Hossain, M., 2015. A review of the literature on open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 5(1), p.6.

Hronszky, I, & Kovács, K. (2013). Interactive Value Production through Living Labs. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 10(2), 89–108.

Huang, HC, Lai, MC, Lin, LH, & Chen, CT. (, 2013). Overcoming organizational inertia to strengthen business model innovation: An open innovation perspective. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 26(6), pp. 977–1002.

Hughes, A. (2009). Innovation and SMEs: Hunting the Snark: Some reflections on the UK experience of support for the small business sector. Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice, 11(1), pp. 114–126.

Hyvonen, S. and M. Tuominen (2006). Entrepreneurial Innovations, Market-Driven Intangibles and Learning Orientation: Critical Indicators for Performance Advantages in SMEs, International Journal of Management and Decision Making, 7(6), pp.643-660.

Idrissia, M, Amaraa, N, & Landrya, R. (2012). SMEs’ degree of openness: the case of manufacturing industries. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 7(1), 186–210.

Inkpen, A., C., Tsang, E.,W.,K. Social Capital, Networks and Knowledge Transfer, Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 2005, pp. 146-165

Jafari, M., Fithian M., Akhavan, P. and Hosnavi,R. Exploring KM features and learning in Iranian SMEs, The Journal of Information and Knowledge Management System, Vol. 37, No.2, pp. 207-218.

Karpak B., Topçu I., (2010) Small medium manufacturing enterprises in Turkey: An analytic network process framework for prioritizing factors affecting success. Int. J. Production Economics, 125, pp.60-70.

Kelley D.J., O’Connor, G.C., Neck,H., Peters,L.(2011) Building an organizational capability for radical innovation:The direct managerial role. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 28, pp. 249–267.

Lee, S., Park, G., Yoon, B., and Park, J. 2010. Open innovation in SMEs: An intermediated network model. Research Policy, 39(2), 290–300.

Lesáková, L. (2014). Evaluating innovations in small and medium enterprises in Slovakia, Contemporary Issues in Business, Management and Education 2013, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 110, pp. 74 – 81

Liu, M., Li, M., Zhang, T. (2012), Empirical Research on China’s SMEs Technology Innovation. Engineering Strategy. Systems Engineering Procedia 5, pp. 372 – 378

McAdam, M, McAdam, R, Dunn, A, & McCall, C. (2014). Development of small and medium-sized enterprise horizontal innovation networks: UK agri-food sector study. International Small Business Journal, 32(7), pp. 830–853.

McEvily, S.,K., Eisenhardt, K.,M.,M., Prescott, J.,E, The global acquisition, leverage, and protection of technological competences, Strategic Management Journal, 25(8/9), 2004, pp. 713-722.

OECD (2000). Bologna 2000 SME Conference. Enhancing the Competitiveness of SMEs through Innovation. Bologna. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/industry/smes/1912543.pdf

OECD (2016), Fostering Markets for SME finance: matching business and investor needs, OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, CFE/SME(2016)4/REV1

Padilla-Meléndez, A, Del Aguila-Obra, AR, & Lockett, N. (2013). Shifting sands: Regional perspectives on social capital’s role in supporting open innovation through knowledge transfer and exchange with small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), pp. 296–318.

Parida, V, Westerberg, M, & Frishammar, J. (2012). Inbound Open Innovation Activities in High‐Tech SMEs: The Impact on Innovation Performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(2), pp. 283–309.

Prajogo, D., I., Ahmed, P.,K. Relationships between innovation stimulus, innovation capacity, innovation performance, R&D Management, 36, 2006, pp. 499-515.

Pullen, AJ, Weerd‐Nederhof, PC, Groen, AJ, & Fisscher, OA. (, 2012). Open innovation in practice: goal complementarity and closed NPD networks to explain differences in innovation performance for SMEs in the medical devices sector. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29(6), pp. 917–934.

Rahman, H, & Ramos, I. (2010). Open Innovation in SMEs: From closed boundaries to the networked paradigm. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 7, pp. 471–487.

Rangone, A. (1999). A Resource-based Approach to Strategy Analysis in Small-medium Sized Enterprises, Small Business Economics12: pp. 233-248.

Rasheed, M.A., Rasheed, M.A., Shahzad, K., Shahzad, K., Conroy, C., Conroy, C., Nadeem, S., Nadeem, S., Siddique, M.U. and Siddique, M.U., 2017. Exploring the role of employee voice between high-performance work system and organizational innovation in small and medium enterprises. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(4), pp.670-688.

Serna, M., Guzman, G.M., Pinzon Castr, S.Y. (2013) The Relationship between Market Orientation and Innovation in Mexican Manufacturing SME’s. Advances in Management & Applied Economics, Volume 3,Issue 5, pp. 125-137.

Singh, H.D.B., 2015. Achieving environmental sustainability of Small and Medium Enterprises through selective supplier development programs. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 4(2), pp.35-50.

Skerlavaja, M., Song,J.H., Youngmin, L. (2010) Organizational learning culture, innovative culture and innovations in South Korean firms, Expert Systems with Applications 37, pp. pp., 6390–6403.

Snoj, B., Millner, B., Gabrijan, V., An Examination of the Relationships among Market Orientation, Innovation Resources, Reputational Resources, and Company Performance in the Transitional Economy of Slovenia, Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 24, 2007, pp. 151-164.

Sok, P., O’Cass, A. (2011). Achieving superior innovation-based performance outcomes in SMEs through innovation resource-capability complementarity. Industrial Marketing Management 40, pp., 1285–1293.

Spithoven, A, Vanhaverbeke, W, & Roijakkers, N. (2013). Open innovation practices in SMEs and large enterprises. Small Business Economics, 41(3), pp. 537–562.

Subrahmanya, B. M.H., (2009) Nature and strategy of product innovations in SMEs: A case the study-based comparative perspective of Japan and India, Innovation: management, policy & practice, Volume 11, pp. 104-113.

Suh, Y, & Kim, MS. (2012). Effects of SME collaboration on R&D in the service sector in open innovation. Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice, 14(3), pp. 349–362.

Suh, Y., and Kim, M.-S. 2014. Effects of SME collaboration on R&D in the service sector in open innovation. Innovation, 14(3), 349–362.

Talebi, K.., Ghavamipour, M., (2012) Innovation in Iran’s small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs): Prioritize influence factors affecting innovation of SMEs, using analytic network process (ANP) method, African Journal of Business Management, Volume 6, No 43, pp. 10775- 10785.

Teirlinck, P & Spithoven, A. (2013). Research collaboration and R&D outsourcing: Different R&D personnel requirements in SMEs. Technovation, 33(4), pp. 142–153.

Theyel, N. (2013). Extending open innovation throughout the value chain by small and medium-sized manufacturers. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), pp. 256–274.

They, N. 2013. Extending open innovation throughout the value chain by small and medium-sized manufacturers. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), 256–274.

Török, Á, & Tóth, J. (2013). Open characters of innovation management in the Hungarian wine industry. Agricultural Economics/Zemedelska Ekonomika, 59(9), pp. 430–439.

van de Vrande, V, De Jong, JP, Vanhaverbeke, W, & De Rochemont, M. (2009). Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation, 29(6), pp. 423–437

Williams, D. and Tsiteladze, D., 2016. Assessing the Value Added by Incubators for Innovative Small and Medium Enterprises in Russia. Technology Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation: Theory Practice Lessons Learned, pp.151-178.

Wynarczyk, P., Piperopoulos, P. and McAdam, M., 2

013. Open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: An overview. International Small Business Journal, 31(3), pp.240-255.

If you are the original writer of this Dissertation Chapter and no longer wish to have it published on the www.ResearchProspect.com then please:

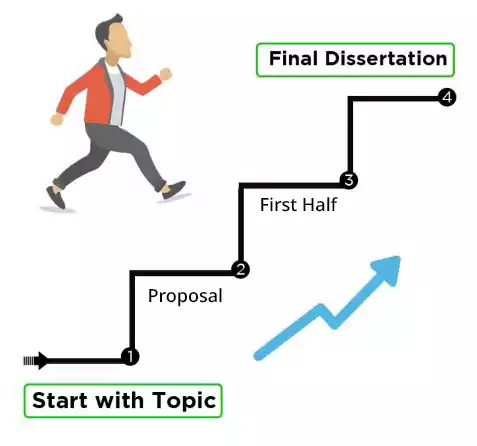

To write the literature review chapter of a dissertation: