The dissertation is the “boss battle” for the vast majority of university-level students across the United Kingdom. This is the task that transitions you from a knowledge-absorbing student to a knowledge producer—a researcher. However, one chapter above all others will drive you to sleepless nights, panic-stricken emails to your supervisors, and bouts of “writer’s block” quicker than any other: the literature review chapter.

Ideally, this section is the anchor of your project. It charts the intellectual territory, acknowledges authors who have done research on the same topic, and shows that your paper is not isolated in a research vacuum. But this is often when optimistic plans meet reality. Assessors have remarked that students struggle to translate their reading into the kind of critical argument that secures a 2:1 or a First.

If you are staring at a stack of research articles and feeling overwhelmed, you are not alone. To help you, we have identified the five most common pitfalls that you can fall into as a student and, more usefully, outlined strategies for how to avoid making mistakes while writing the literature review for a dissertation.

Table of Contents

1: The “Laundry List” Approach

When writing your literature review, always ask yourself: Is this a real, in-depth subject literature review, or a “He said, she said” summary? It is easy to fall straight into this trap. This happens when you treat your review like a checklist, featuring one author in one paragraph and the next author in the next paragraph and so on. Instead of creating a cohesive reflection, you are simply taking a roll call.

“Smith (2019) found that remote work increases efficiency. Jones (2020) discovered that remote work makes people lonely. Brown (2021) noted that it depends on the job role.”

The problem here is that you are showing your audience the pieces of the puzzle, but never completing it yourself. This way, you are showing that you can read, but you lack the ability to put concepts together. A literature review is not supposed to be a summary of your reading; it must be a synthesis.

Looking for research help?

Research Prospect to the rescue then!

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with their research across a variety of disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

How to Fix It: The Synthesis Matrix

Try not to think about who wrote these papers and focus on what they are trying to convey. For example, suppose that you are hosting a dinner party, where you invite all your authors. Would you just let them sit around in silence, giving each other monologues? Or would you prefer if they engaged in a discussion?

Make a synthesis matrix before you start writing. All you need to do is create a simple table, where you will assign each row to one author, and you will fill in the columns with themes or variables, for instance. The rule is: Read vertically, write horizontally. Fill in the rows as you read the papers, and once you start writing, look down the columns.

For example, if Smith and Jones disagree, put them in the same paragraph and explain why. A synthesised version looks different:

“The impact of remote work is contested. While Smith (2019) argues it drives efficiency, Jones (2020) suggests this comes at the cost of employee well-being. Brown (2021) offers a middle ground, arguing that the outcome depends entirely on the sector.”

Notice the difference? Now you are telling a story about the topic, not presenting a list of authors. The transition from author-centric to theme-centric writing is the foundation of a good dissertation.

2: Over-Reliance on Secondary Sources

We have all found ourselves in this position at least once while doing research. You are short on time, and you see a great quote in a textbook which encapsulates a complex theory by Foucault. It is so tempting to simply quote the textbook.

In academia, this is like playing the telephone game. Each time a researcher reports on someone else’s work, their ideas are filtered through their understanding. If Johnson got it slightly wrong or oversimplified it, and you cite that paper, the mistake is passed on.

The Spinach Myth

Think about the well-known myth surrounding spinach. For years, people thought that spinach was a miracle source of iron because somebody performed some calculations in the 19th century. As it turns out, that conviction was wrong—either there was a mistake in the calculations, or a researcher misinterpreted the findings later on; and so, as time passed, the mistake became a “fact”.

How to Fix It: Be an Academic Detective

If you come across an excellent summary in a journal article, check their reference list for the original paper and read it yourself. This way, even if you only read the abstract, methods, and conclusion of the original, you are getting the information from the horse’s mouth.

To demonstrate thorough scholarship, it is crucial to focus on primary sources for your dissertation, particularly in the literature review chapter. Over-reliance on secondary sources suggests a lack of engagement with the original texts and may be perceived as lazy. Secondary sources should be reserved for providing general definitions, typically in the introduction chapter.

3: Accepting Findings as Facts

There is a tendency among students to treat peer-reviewed journals as holy writ. The mere fact that it is published in a journal does not mean it is absolutely true or applicable to anything and everything. A descriptive review simply states what previous studies have discovered. A critical review goes further—it ascertains the validity of the findings.

If, for example, you cite a study that deems a new teaching method to be revolutionary, but you fail to mention in your discussion that it was only tested on 10 pupils in one school, you have missed the trick.

How to Fix It: Interrogate the Methodology

You have to become a critic. When reviewing a paper, you need to concentrate on the how, rather than the what.

- Sample size: Is it big enough to allow for a generalisation?

- Context: When and where was the paper written? Can a 2015 study on social media remain relevant today?

- Bias: Who sponsored the research?

For instance, while analysing quantitative studies, you must verify whether the results were actually significant, as suggested by the authors. You can use a probability calculator to assess the possibility of these results occurring by chance. Always question the findings of studies that claim a significant effect if the sample size appears insufficient to support such a claim. By adding this extra depth to your literature review, you are showing good critical thinking skills, which might push your dissertation over that First-Class threshold.

4: Ignoring Grey Literature

When you begin your search, you probably go directly to Google Scholar or university libraries and look only for peer-reviewed journals. Although important for validity and credibility, this leads to publication bias.

Publishing academic papers takes a lot of time. It could take anywhere between a couple of months to several years before the article you’ve submitted is published. And if you are writing about a fast-moving topic, even the most recent research is most likely already outdated. In addition, journals tend to prefer positive findings—if you only read those, you get half of the story.

How to Fix It: Widen Your Net

To make your review comprehensive, you need to include grey literature. This type of paper is not influenced by commercial publishing. If you are writing your dissertation for a UK university, consider including the following types of sources:

- Government white papers: Crucial for Law, Sociology, and Education students.

- Theses and dissertations: PhD and Master’s theses written by other people are goldmines. They usually include the “null results” that journals refuse to publish, and you can scan through their biographies for sources that you might have missed when doing your research.

- Industry reports: Data collected by the World Bank, the NHS, McKinsey, or CIPD, for example, are often more up-to-date than scholarly sources.

By including these sources, you show the marker that you are in touch with the real world, not just the ivory tower.

Mistake 5: Failing to Identify the Gap

This is probably the most heartbreaking mistake you can make as a student. You write a great, critical, well-synthesised review… and then just stop. You wind up a chapter simply stating something like, “In conclusion, many people have written about this.”

So what?

Your literature review is not an isolated entity; its sole purpose is to justify why your study is important and needs to be conducted. If your chapter does not inform your reader of the gap that it is trying to fill, it has not fulfilled its primary purpose.

How to Fix It: The Funnel and the Bridge

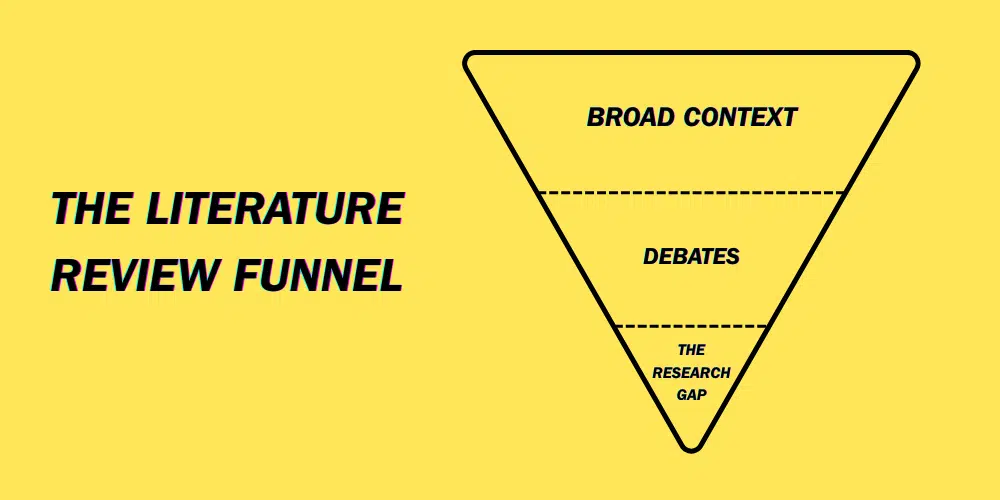

Visualise your chapter as a funnel.

- Top: Start broad with the general context and history.

- Middle: Narrow down to specific themes and current debates.

- Bottom: Present the research gap.

Your audience might not notice the void unless you explicitly say what’s missing. Maybe you have discovered a methodological or contextual gap? Your conclusion shouldn’t just summarise what you said—it should act as a bridge between your review and your research questions.

“While existing literature has extensively covered X (Smith, 2019) and Y (Jones, 2020), there remains a paucity of research regarding Z. Consequently, this study aims to address this gap by…”

This creates a seamless transition into your methodology chapter and preserves the golden thread of your argument.

Frequently Asked Questions

There is no hard rule, but in the UK, it is usually recommended to limit the literature review to around 20-30% of the total word count. That is 2,000 to 3,000 words for a standard undergraduate dissertation and about 4,000 words for a Master’s thesis. Always check your module handbook to ensure that your paper meets the formal requirements of your degree.

No, that is impossible and a recipe for burnout. You need to be smart.

- Scan the abstract: Is it relevant?

- Read the conclusion: What did they actually find?

- Check the methodology: Is it reliable?

Only read the full text if the paper is absolutely central to your argument or if you are planning to replicate their method.

Conventionally, scientific disciplines use the passive voice; social sciences and humanities, on the other hand, are gradually opening to the use of the first person. While you can use “I” to make your writing more active and assertive, always check if it is allowed in your department.